With the rise of data-driven business models, data privacy and data protection came into sharper focus. Recent regulations such as the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR, introduced in 2018, adopted and supplemented by national legislation) and Switzerland’s new data protection law (nFADP, German: revDSG, effective since September 2023) granted individuals more control about the personal data that organizations store about them – and at the same time established clear obligations for organizations concerning the personal data they collect, store and process.

In particular, individuals have the right to request from a given organization suitable information on which data it has stored about them and how these data are processed; the right to request the correction of incorrect personal data; and finally, the right to request deletion of their personal data (the so-called right to be forgotten, which, however, may in some cases be restricted by conflicting regulation defining retention periods for certain types of data). The respective organization, in turn, has to respond properly and quickly to such a request. This obligation can be quite challenging for organizations, as they have to be able to find and delete all relevant personal data across all their systems containing any personal data.

Finding the needle in the haystack

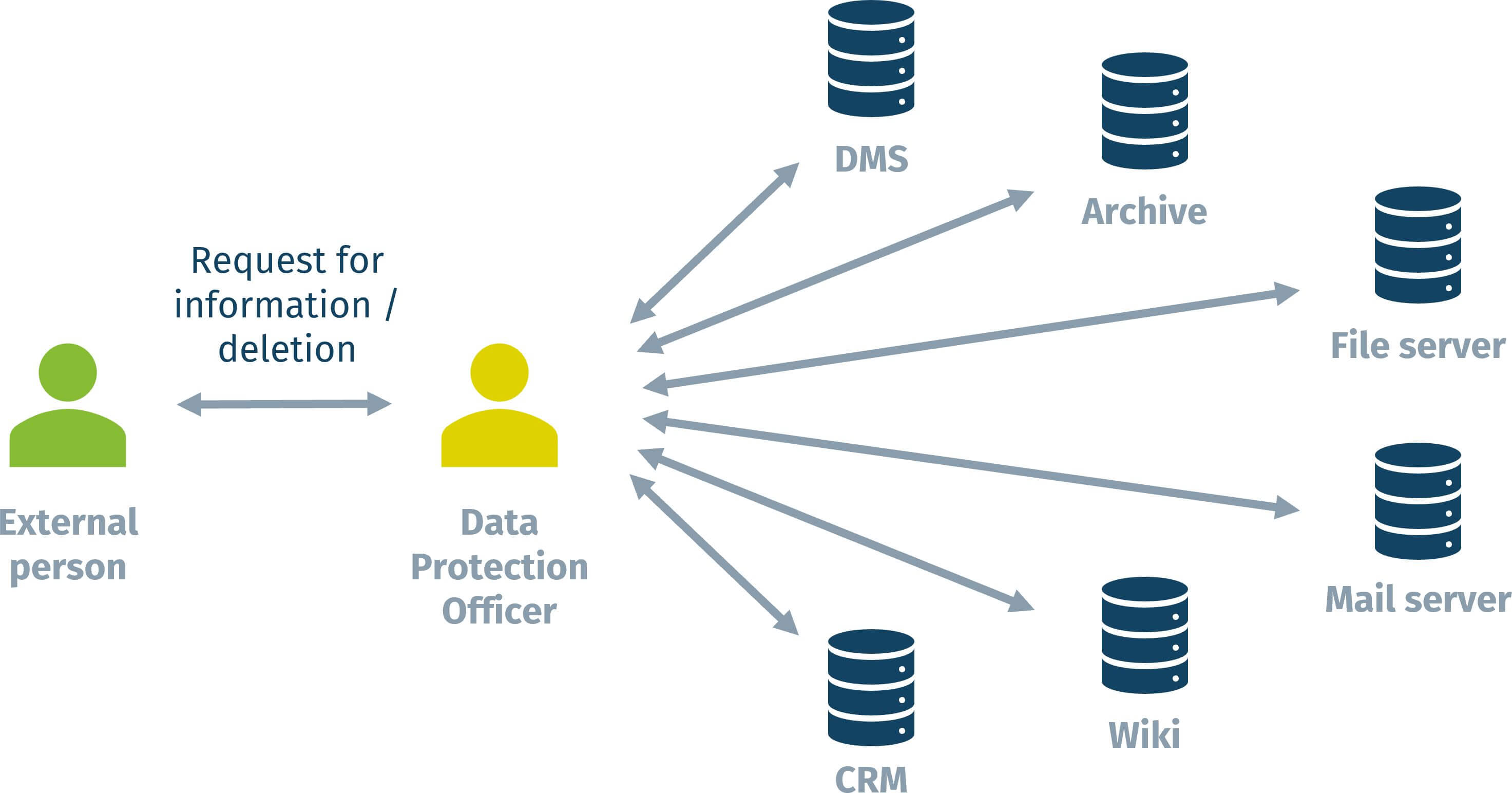

In most organizations, the situation currently looks like this: When the organization receives from an external person a request for information on their personal data, its Data Protection Officer (DPO) manually searches, one by one, all relevant systems that might potentially contain personal data.

If the DPO is lucky, there are no physical documents to be searched and all relevant systems have a decent search functionality. But even then, browsing all these systems can be a rather time-consuming, even tedious task. Organizations are well-advised to reduce the number of systems in which they store personal data to simplify the problem. This is a good idea, anyway, as GDPR and nFADP also require them to fully control and document how, where and for how long personal data are stored. However, if the organization’s business model is not to be affected, personal data will almost inevitably be stored in more than just one or two systems.

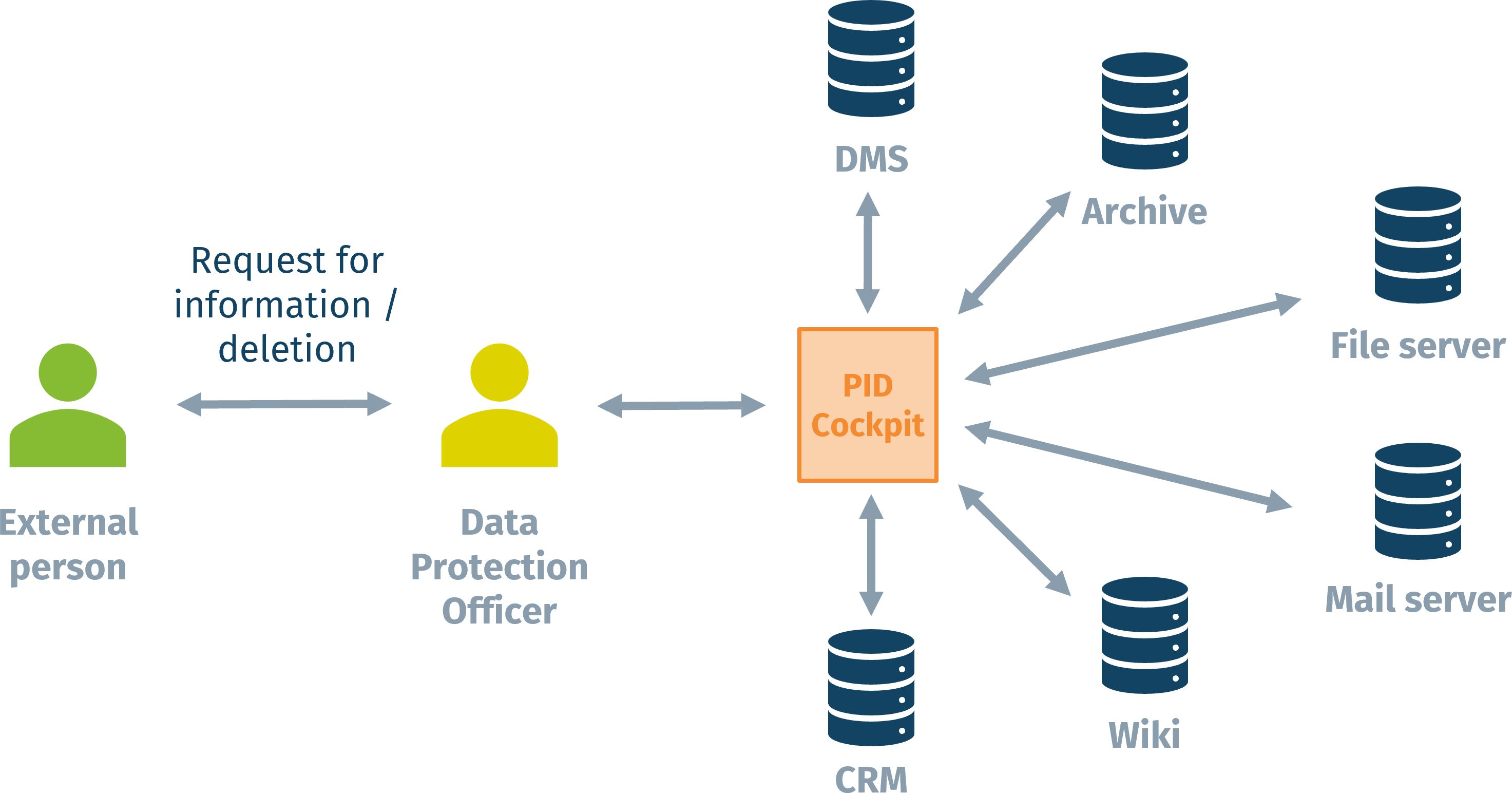

A better strategy is needed – at least if the organization expects more than just a handful of such requests per year. Below, we outline an approach consisting of several steps, each providing a further improvement over the status quo. This strategy was also adopted by Karakun when creating our own PID Cockpit – the term “PID” here refers to “personal identifiable data”, which is the more formal term for personal data (sometimes also called “personal identifiable information”, PII).

Improvement 1: Use a centralized search tool

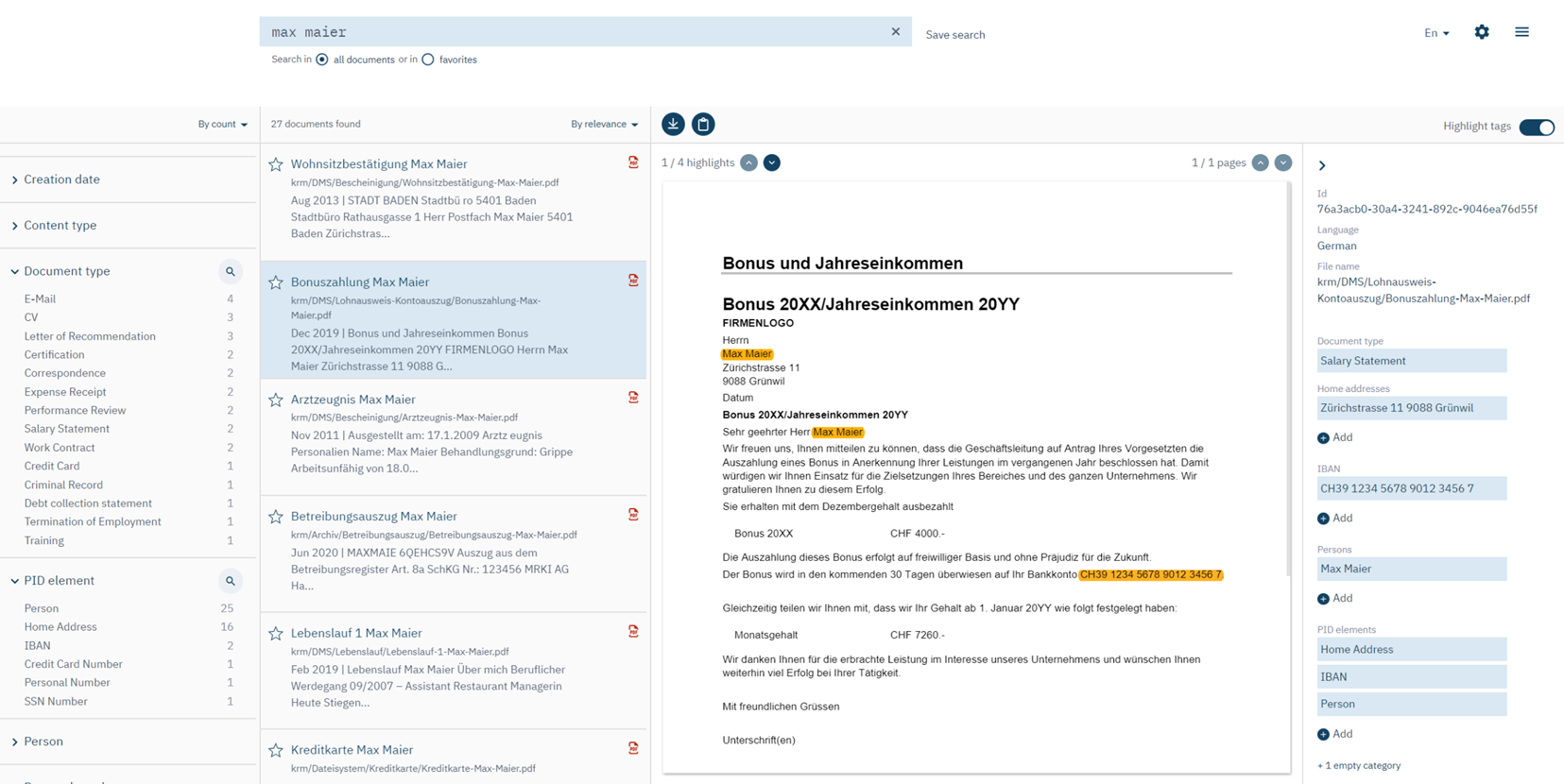

Using a single search solution is the most natural improvement to this situation. That way, the DPO can process the request by a single search query in a single system that will find personal data in all relevant systems. Aside from saving a lot of time, this also has the desirable effect that all systems are searched consistently with the same query parameters.

Technically, to enable this approach, the relevant source systems need to be integrated with the PID Cockpit such that it can index their documents (and other content elements). This communication happens whenever documents are added/modified/deleted in the source system – and it can be triggered either by the source system (calling the Cockpit’s web API) or by the Cockpit (calling the source system’s API at configurable poll intervals).

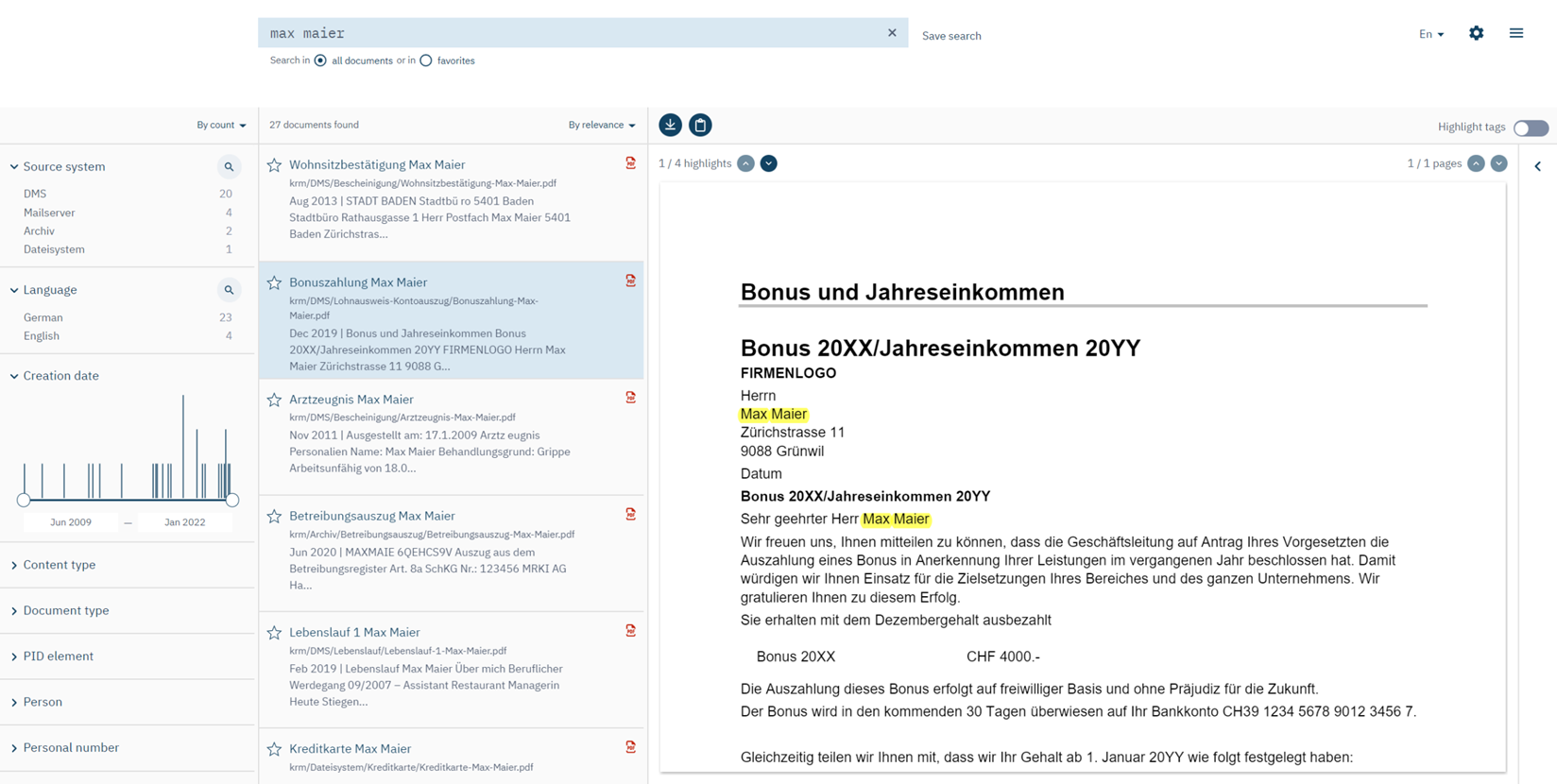

Improvement 2: Inspect documents directly in the UI

To decide whether a document is relevant to the person’s request, the DPO also has to inspect the document’s content. A suitable solution has to be designed with care to support the DPO well. As you probably know from your own experience, with many search solutions (including web search engines such as Google), clicking an individual search result will open the respective document (or web page) outside the search UI (in a separate browser tab or application, e.g., a PDF reader). The user then has to search inside that document to find the relevant text locations and assess these for their relevance. This means two things: The user effectively has to search twice (first searching for documents, second searching for text locations inside every document), and they repeatedly leave the context of their original document search which requires more attention on the user’s part to ensure a systematic inspection of search results.

With our recommended approach, a DPO doesn’t need to switch context and there is no second round of searching. The DPO can inspect documents inside the search UI next to the result list. To this end, the PID Cockpit has an embedded document viewer. Moreover, the Cockpit highlights the search terms in the opened document and allows the DPO to easily step through them instead of searching again.

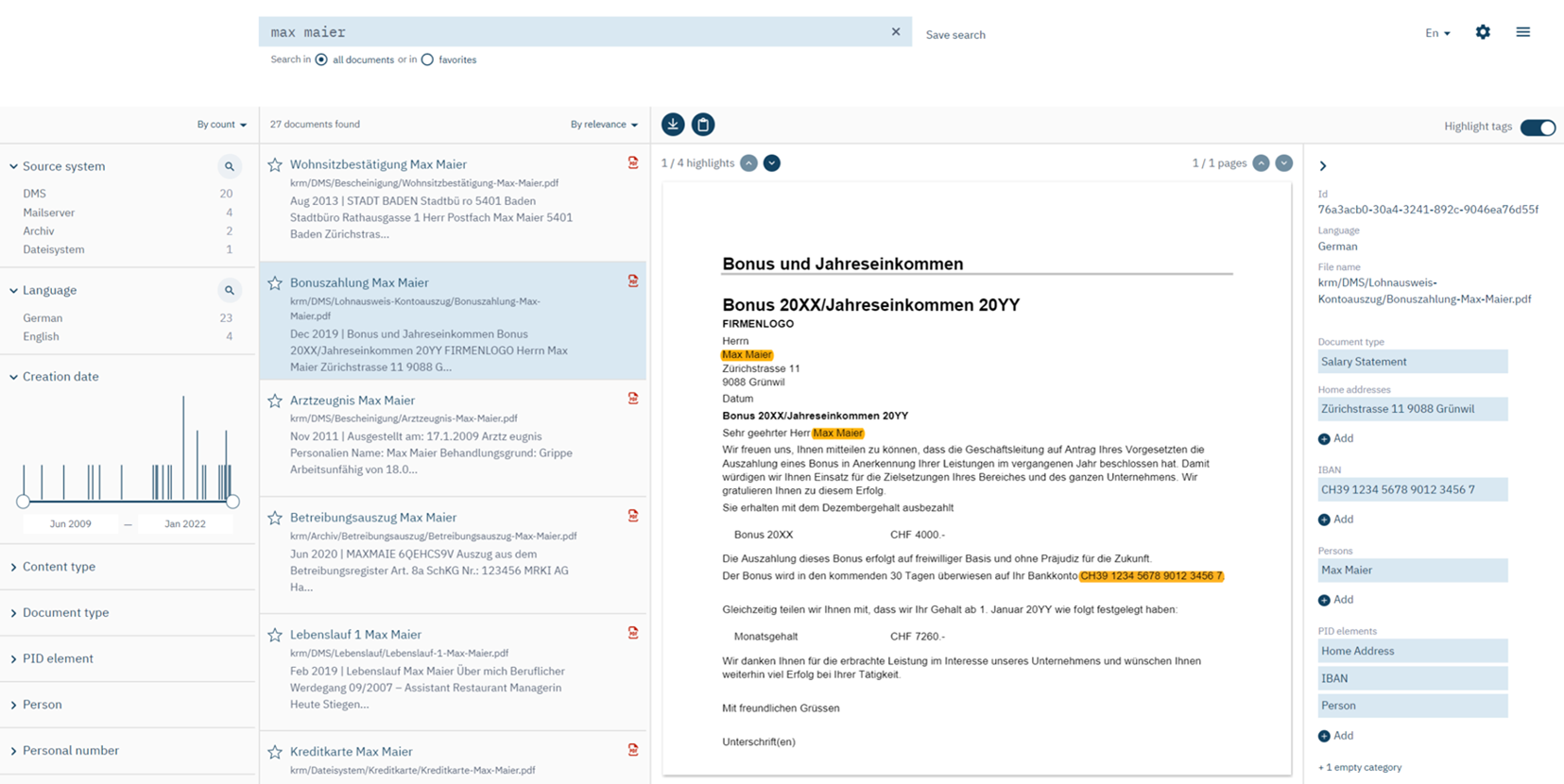

Improvement 3: Language technology to detect personal data

What would the DPO search for in the source systems (via the PID Cockpit)? Usually, this will be the respective person’s name. The search results will be documents that mention this name. That’s a good starting point, for anything else in those documents may then relate to that person and thus potentially constitute personal data. However, many known types of personal data might occur nowhere near the person’s name and are hard to search for. In particular, if the DPO does not know about them. Some examples are postal addresses, email addresses, bank account numbers, credit card data, social security numbers etc.

To support DPOs in handling and finding these types of personal data, we employ two types of Natural Language Processing (NLP) methods:

- Information extractors to detect any type of personal data within the documents’ content;

- Text classifiers to determine the document type for each document by its content (e.g. CV, certification, contract, salary statement). The motivation here is that some documents are, by nature, sensible in general (e.g., medical records).

In the PID Cockpit, the results of these analyses are listed to the right of the opened document. Additionally, the extracted personal data are highlighted inside the document so the DPO can easily step through them. That way, the DPO can quickly inspect all the sections of a document that may be of interest to the given request for information. This is particularly useful for large documents.

Improvement 4: Targeted search using filters

Improvement 3 essentially enriches each document by its type and extracted personal data. These data are important when inspecting a document individually. But they are even more useful at the global level: Let’s assume the DPO finds it most efficient to inspect the resulting documents in batches: e.g., first all emails, then all CVs, etc. Or maybe the given person has asked only for certain types of stored documents (e.g. only medical records) or certain types of stored personal data (e.g., bank account numbers and credit card data). In all these cases, the DPO would be best supported if the tool would allow them to filter the search result set to documents of a specific document type and/or documents containing specific types of personal data.

Therefore, as improvement 4, our strategy recommends providing the DPO with search filters for all document types and for all types of personal data that the system automatically enriched the documents with.

Additionally, many of the original document metadata (that existed before the enrichment step) also constitute good candidates for search filters, e.g., source system, file format, creation date, and document language. These, too, can help the DPO to structure their inspection or to reduce the number of documents that need to be inspected in the first place. For instance, if the given person used to work at the DPO’s organization from 2019 through 2021, then the DPO might want to filter the documents for their creation date.

Improvement 5: Workflow support

The improvements described above involve information retrieval and NLP. Of course, this is not a surprise because the task of the DPO is all about searching and assessing textual content. However, the workflow of the DPO extends beyond searching and assessing, so the DPO can be assisted even further. There are many ways in which the software can support this workflow. Below, we give two examples.

The first example is about the fact that not all documents in the result set are relevant to the given request for information. For instance, some documents might not even concern the given person (especially if there are documents on another person with the same name, e.g. another employee or the employee of some other company that the DPO’s organization does business with). Therefore, while inspecting the documents in the result set, the DPO will typically want to somehow collect those documents that seem relevant to the given request. The PID Cockpit provides a simple and intuitive way to do so – by marking documents directly in the search results. Once the DPO is done going through the result set, they can review all marked documents as a list (which may be searched and filtered, if needed).

As the second example, consider that the DPO typically needs to produce some kind of report describing, at the required level of abstraction, the types of personal data the organization has stored about the given person. There might even be the need to create two report types: an internal one (e.g., for auditing purposes) and an external one (to be shared with the given person). The PID Cockpit allows the user to generate either type of report by simply clicking a button.

Conclusion

The PID Cockpit is a vital tool for organizations seeking to comply with data protection regulations, including GDPR and Switzerland’s new data protection law.

Organizations are well advised to store personal data only electronically – and in as few different software systems as possible without compromising their business needs. Moreover, organizations expecting more than a handful of requests for information per year should consider using a software tool to assist their DPO in processing these requests and to ensure timely, accurate, and compliant responses. This paper described a general strategy for building a suitable software tool like Karakun’s PID Cockpit.

At the technological level, the strategy described above is not a groundbreaking innovation. Instead, it is a practical solution to a fairly new problem that most organizations have to deal with – and this practical solution applies well-established technologies such as information retrieval and NLP and thereby demonstrates that one does not have to look at currently hyped technologies to deliver a great deal of value.