Since Java 8 we have a new date & time API as part of Java. The API is really good and offers a lot of functionality and flexibility. It makes it much easier to handle date and time information in Java. But even with this new API there are several use cases that are still quite complex.

When talking about problems with date and time information we normally think of timezones first. In this post I will show you that even the basic usage of date information can create problems.

Let’s forget about all the timezone problems for now and have a look at a really easy use case: We want to print the year of a date. Maybe even this task can end in some trouble…

Let’s have a look at a simple code snippet:

final LocalDate myDate = LocalDate.of(2015, 11, 30);

final DateTimeFormatter formatter = DateTimeFormatter.ofPattern("dd.MM.YYYY");

final String formattedDate = formatter.format(myDate);

System.out.println("The date is " + formattedDate);Even if you have not used the API that often it’s quite easy to understand that the code will print The date is 30.11.2015 to the console. Based on this experience we can create a method like this:

/**

* Prints the given date in the format that is normally used in europe.

* The format is described as

* [day of month (2 digits)].[month of year (2 digits)].[year (4 digits)]

*

* @param date the date

*/

public static void printDate(final LocalDate date) {}

final DateTimeFormatter formatter = DateTimeFormatter.ofPattern("dd.MM.YYYY");

final String formattedDate = formatter.format(myDate);

System.out.println("The date is " + formattedDate);

}What if I tell you that this code already contains a common problem that I’ve seen in several projects within the last years? To understand that problem we should call the method with a set of different dates:

LocalDate.of(2015, 11, 30)results inThe date is 30.11.2015LocalDate.of(1992, 4, 12)results inThe date is 12.04.1992LocalDate.of(2008, 12, 28)results inThe date is 28.12.2008LocalDate.of(2021, 1, 1)results inThe date is 01.01.2020

If you realized the mismatch and you are not aware of the problem you might ask yourself what the hell is happening here. While the first 3 examples look good the output of the last one contains a wrong year. You can easily try this on your own if you do not believe me… ;)

It’s not a bug, it’s a feature

To be true the described behavior is not a bug in the JDK, it’s a feature that a lot of people are not aware of. So let’s have a look at why the given output is incorrect and what we need to do to get our wanted behavior.

The problem with our code is hidden in the usage of the DateTimeFormatter. To receive our date as a formatted string we use the pattern dd.MM.YYYY. Maybe you already asked yourself why the d in the pattern is written lowercase while the M and Y are written uppercase. Let’s have a look at the JavaDoc of the DateTimeFormatter class and the definition of the pattern for formatting and parsing. In this documentation, you can find a table with a description of each supported letter in such pattern. The following table contains only the letters that are interesting for our use case:

| letter | meaning | examples |

|---|---|---|

| d | day-of-month | 10 |

| D | day-of-year | 189 |

| m | minute-of-hour | 30 |

| M | month-of-year | 7; 07 |

| y | year-of-era | 2004; 04 |

| Y | week-based-year | 1996; 96 |

| u | year | 2004; 04 |

For all the letters that we used in the example the uppercase and lowercase variants have a different meaning. When having a look at the definition for day and month we can easily say that we have chosen the right pattern to format the string. It becomes more interesting when having a look at the year definition. As you can see the table contains 3 different letters (y, Y and u) that can be used to define the format of a year in the pattern.

Finding the problem

In our example we used YYYY to define the year. Let’s have a look at the definition of the parser letter Y. As you can see in the table it is defined as ‘week-based-year’. While the examples in the table looks fine this definition is the cause of our problem:

The ‘week-based-year’ type is defined by the ‘ISO week date’ that is part of ISO 8601. A detailed definition of this standard can be found at Wikipedia. The standard defines that a year has 52 or 53 full weeks which means 364 or 371 days instead of the usual 365 or 366 days. In the definition, weeks always start with a Monday and the first week of a year is the week that contains the first Thursday of the year.

By using this definition it can happen that the first days of a year are not part of the first week of the year but of the last week of the previous year. Plus, the last days of December could be part of the first week of the next year. Here are some examples:

- December 29, 2014 (Monday) is defined as part of the first week of the year 2015 since the Thursday of this week is the first Thursday in 2015 (1 January 2015). Based on this the

YYYYpattern would result in 2015 for that date. - January 1, 2015 (Thursday) is defined as part of the first week of the year 2015 since the Thursday of this week is the first Thursday in 2015. Based on this the

YYYYpattern would result in 2015 for that date. - January 1, 2016 (Friday) is defined as part of the last week of the year 2015 since the Thursday of this week is in 2015 (December 31, 2015). Based on this the

YYYYpattern would result in 2015 for that date.

Maybe you have noticed in the samples that both dates ‘1 January 2015’ and ‘1 January 2016’ will result in the same string by using the dd.MM.YYYY pattern… ;)

For most people this ISO standard is not usable for their regular work. But as you have seen in the examples this can end in critical bugs in our software.

Since we found the problem and understood the ‘ISO week date’, we can say that this is normally not the solution that we want to use in our software. The DateTimeFormatter class supports 2 other letters (y and u) to format year information. Let’s have a look at these 2 options.

Working with eras

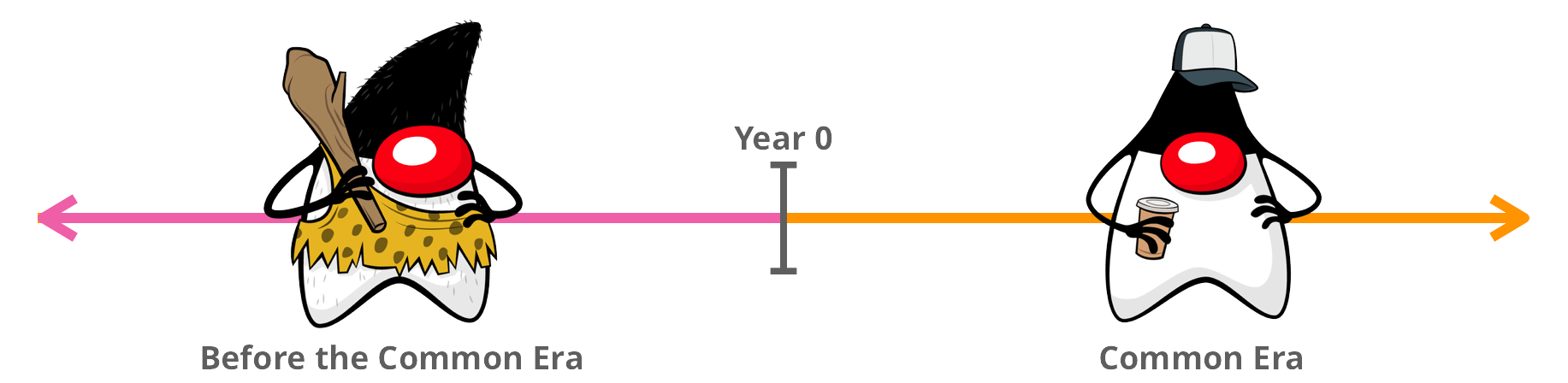

It might look like there is no difference if you use y or u as a letter for years. As long as the date is within the current era everything is fine. The Gregorian Calendar uses the “Common Era” notation where the 2 eras “Common Era” (CE) and “Before the Common Era” (BCE) are used. We are currently in the “Common Era” that started with year 0. An end of the “Common Era” is not defined. This definition is an alternative to Dionysian “Before Christ” (BC) and “Anno Domini” (AD) definition that is numerically equivalent but uses a different (non religious based) wording.

When formatting a year by using the DateTimeFormatter class you can add the the era to your custom pattern. The era is defined by the letter G as you can find out in the JavaDoc of DateTimeFormatter. The following table gives an overview about how years will be formatted based on the 2 different types:

| year (as number) | pattern ‘uuuu’ | pattern ‘yyyy’ | pattern ‘yyyy G’ |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2019 | 2019 | 2019 AD |

| 3 | 0003 | 0003 | 0003 AD |

| 0 | 0000 | 0001 | 0001 BC |

| -1 | -0001 | 0002 | 0002 BC |

| -10 | -0010 | 0011 | 0011 BC |

| -2019 | -2019 | 2020 | 2020 BC |

From my point of view, both pattern have it’s downsides. When using the yyyy pattern without adding information of the era you might get an output that will be interpreted wrong by an user. Imagine you have a mathematical bug in your software and calculate the year ‘-2019’ as the final year of any contract. I would assume that it will be better to see ‘-2019’ on screen / paper and recognise the error instead of ‘2020’.

Another interesting point is that the result might be longer as the letter count in the uuuu pattern. As you can see in the table negative year numbers will have a - as prefix when using the uuuu pattern. This means you cannot trust the string length of a formatted date when using the u to format years.

Other eras in Java

Java supports different calendar systems next to the Gregorian Calendar. You can find a good example when having a look at the JapaneseChronology class that defines the ‘Japanese Imperial calendar system’ in Java. While I have absolutely no clue about that calendar system you can find out that is has several eras that are defined by the JapaneseEra class. This class contains several constants that defines the eras of the calendar system:

| name | meaning |

|---|---|

| MEIJI | The ‘Meiji’ era (1868-01-01 - 1912-07-29) |

| TAISHO | The ‘Taisho’ era (1912-07-30 - 1926-12-24) |

| SHOWA | The ‘Showa’ era (1926-12-25 - 1989-01-07) |

| HEISEI | The ‘Heisei’ era (1989-01-08 - current) |

When using the ‘Japanese Imperial calendar system’ Java offers some additional classes to define time information. The following code creates a date based on the calendar and prints it based on different format pattern strings:

final JapaneseDate japaneseDate = JapaneseDate.of(JapaneseEra.MEIJI, 7, 3, 17);

final String format1 = DateTimeFormatter.ofPattern("dd.MM.uuuu").format(japaneseDate);

final String format2 = DateTimeFormatter.ofPattern("dd.MM.yyyy").format(japaneseDate);

final String format3 = DateTimeFormatter.ofPattern("dd.MM.yyyy G").format(japaneseDate);

System.out.println(format1); // prints '17.03.1874'

System.out.println(format2); // prints '17.03.0007'

System.out.println(format3); // prints '17.03.0007 Meiji'In this sample the usage between the two pattern yyyy and uuuu ends in a totally different result.

Conclusion

Working with date and time information is always a complex topic. Normally people say that coding will become complex when timezone functionality is added. In the given examples we did not address timezones at all and already found a lot of complex topics. All these topics can end in horrible bugs in business applications.

For the initial problem we can easily say that the dd.MM.YYYY pattern should never be used. If you want to use dd.MM.yyyy or dd.MM.uuuu in your application depends on your needs and how you want to visualize negative year information. Just saying that your application will never need to handle negative years is maybe not the best answer since we are all just developers that create bugs from time to time. ;)